Can Bundler Be as Fast as uv?

Dec 29, 2025 @ 12:26 pmAt RailsWorld earlier this year, I got nerd sniped by someone. They asked “why can’t Bundler be as fast as uv?” Immediately my inner voice said “YA, WHY CAN’T IT BE AS FAST AS UV????”

My inner voice likes to shout at me, especially when someone asks a question so obvious I should have thought of it myself. Since then I’ve been thinking about and investigating this problem, going so far as to give a presentation at XO Ruby Portland about Bundler performance. I firmly believe the answer is “Bundler can be as fast as uv” (where “as fast” has a margin of error lol).

Fortunately, Andrew Nesbitt recently wrote a post called “How uv got so fast”, and I thought I would take this opportunity to review some of the highlights of the post and how techniques applied in uv can (or can’t) be applied to Bundler / RubyGems. I’d also like to discuss some of the existing bottlenecks in Bundler and what we can do to fix them.

If you haven’t read Andrew’s post, I highly recommend giving it a read. I’m going to quote some parts of the post and try to reframe them with RubyGems / Bundler in mind.

Rewrite in Rust?

Andrew opens the post talking about rewriting in Rust:

uv installs packages faster than pip by an order of magnitude. The usual explanation is “it’s written in Rust.” That’s true, but it doesn’t explain much. Plenty of tools are written in Rust without being notably fast. The interesting question is what design decisions made the difference.

This is such a good quote.

I’m going to address “rewrite in Rust” a bit later in the post.

But suffice to say, I think if we eliminate bottlenecks in Bundler such that the only viable option for performance improvements is to “rewrite in Rust”, then I’ll call it a success.

I think rewrites give developers the freedom to “think outside the box”, and try techniques they might not have tried.

In the case of uv, I think it gave the developers a good way to say “if we don’t have to worry about backwards compatibility, what could we achieve?”.

I suspect it would be possible to write a uv in Python (PyUv?) that approaches the speeds of uv, and in fact much of the blog post goes on to talk about performance improvements that aren’t related to Rust.

Installing code without eval’ing

pip’s slowness isn’t a failure of implementation. For years, Python packaging required executing code to find out what a package needed.

I didn’t know this about Python packages, and it doesn’t really apply to Ruby Gems so I’m mostly going to skip this section.

Ruby Gems are tar files, and one of the files in the tar file is a YAML representation of the GemSpec.

This YAML file declares all dependencies for the Gem, so RubyGems can know, without evaling anything, what dependencies it needs to install before it can install any particular Gem.

Additionally, RubyGems.org provides an API for asking about dependency information, which is actually the normal way of getting dependency info (again, no eval required).

There’s only one other thing from this section I’d like to quote:

PEP 658 (2022) put package metadata directly in the Simple Repository API, so resolvers could fetch dependency information without downloading wheels at all.

Fortunately RubyGems.org already provides the same information about gems.

Reading through the number of PEPs required as well as the amount of time it took to get the standards in place was very eye opening for me. I can’t help but applaud folks in the Python community for doing this. It seems like a mountain of work, and they should really be proud of themselves.

What uv drops

I’m mostly going to skip this section except for one point:

Ignoring requires-python upper bounds. When a package says it requires python<4.0, uv ignores the upper bound and only checks the lower. This reduces resolver backtracking dramatically since upper bounds are almost always wrong. Packages declare python<4.0 because they haven’t tested on Python 4, not because they’ll actually break. The constraint is defensive, not predictive.

I think this is very very interesting. I don’t know how much time Bundler spends on doing “required Ruby version” bounds checking, but it feels like if uv can do it, so can we.

Optimizations that don’t need Rust

I really love that Andrew pointed out optimizations that could be made that don’t involve Rust. There are three points in this section that I want to pull out:

Parallel downloads. pip downloads packages one at a time. uv downloads many at once. Any language can do this.

This is absolutely true, and is a place where Bundler could improve. Bundler currently has a problem when it comes to parallel downloads, and needs a small architectural change as a fix.

The first problem is that Bundler tightly couples installing a gem with downloading the gem. You can read the installation code here, but I’ll summarize the method in question below:

def install

path = fetch_gem_if_not_cached

Bundler::RubyGemsGemInstaller.install path, dest

end

The problem with this method is that it inextricably links downloading the gem with installing it.

This is a problem because we could be downloading gems while installing other gems, but we’re forced to wait because the installation method couples the two operations.

Downloading gems can trivially be done in parallel since the .gem files are just archives that can be fetched independently.

The second problem is the queuing system in the installation code. After gem resolution is complete, and Bundler knows what gems need to be installed, it queues them up for installation. You can find the queueing code here. The code takes some effort to understand. Basically it allows gems to be installed in parallel, but only gems that have already had their dependencies installed.

So for example, if you have a dependency tree like “gem a depends on gem b which depends on gem c” (a -> b -> c), then no gems will be installed (or downloaded) in parallel.

To demonstrate this problem in an easy-to-understand way, I built a slow Gem server.

It generates a dependency tree of a -> b -> c (a depends on b, b depends on c), then starts a Gem server.

The Gem server takes 3 seconds to return any Gem, so if we point Bundler at this Gem server and then profile Bundler, we can see the impact of the queueing system and download scheme.

In my test app, I have the following Gemfile:

source "http://localhost:9292"

gem "a"

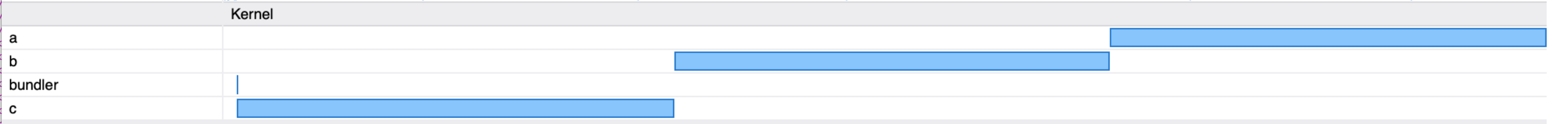

If we profile Bundle install with Vernier, we can see the following swim lanes in the marker chart:

The above chart is showing that we get no parallelism during installation.

We spend 3 seconds downloading the c gem, then we install it.

Then we spend 3 seconds downloading the b gem, then we install it.

Finally we spend 3 seconds downloading the a gem, and we install it.

Timing the bundle install process shows we take over 9 seconds to install (3 seconds per gem):

> rm -rf x; rm -f Gemfile.lock; time GEM_PATH=(pwd)/x GEM_HOME=(pwd)/x bundle install

Fetching gem metadata from http://localhost:9292/...

Resolving dependencies...

Fetching c 1.0.0

Installing c 1.0.0

Fetching b 1.0.0

Installing b 1.0.0

Fetching a 1.0.0

Installing a 1.0.0

Bundle complete! 1 Gemfile dependency, 3 gems now installed.

Use `bundle info [gemname]` to see where a bundled gem is installed.

________________________________________________________

Executed in 11.80 secs fish external

usr time 341.62 millis 231.00 micros 341.38 millis

sys time 223.20 millis 712.00 micros 222.49 millis

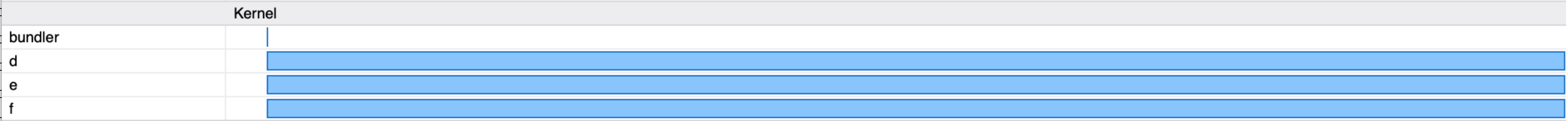

Contrast this with a Gemfile containing d, e, and f, which have no dependencies, but still take 3 seconds to download:

source "http://localhost:9292"

gem "d"

gem "e"

gem "f"

Timing bundle install for the above Gemfile shows it takes about 4 seconds:

> rm -rf x; rm -f Gemfile.lock; time GEM_PATH=(pwd)/x GEM_HOME=(pwd)/x bundle install

Fetching gem metadata from http://localhost:9292/.

Resolving dependencies...

Fetching d 1.0.0

Fetching e 1.0.0

Fetching f 1.0.0

Installing e 1.0.0

Installing f 1.0.0

Installing d 1.0.0

Bundle complete! 3 Gemfile dependencies, 3 gems now installed.

Use `bundle info [gemname]` to see where a bundled gem is installed.

________________________________________________________

Executed in 4.14 secs fish external

usr time 374.04 millis 0.38 millis 373.66 millis

sys time 368.90 millis 1.09 millis 367.81 millis

We were able to install the same number of gems in a fraction of the time. This is because Bundler is able to download siblings in the dependency tree in parallel, but unable to handle other relationships.

There is actually a good reason that Bundler insists dependencies are installed before the gems themselves: native extensions.

When installing native extensions, the installation process must run Ruby code (the extconf.rb file).

Since the extconf.rb could require dependencies be installed in order to run, we must install dependencies first.

For example nokogiri depends on mini_portile2, but mini_portile2 is only used during the installation process, so it needs to be installed before nokogiri can be compiled and installed.

However, if we were to decouple downloading from installation it would be possible for us to maintain the “dependencies are installed first” business requirement but speed up installation.

In the a -> b -> c case, we could have been downloading gems a and b at the same time as gem c (or even while waiting on c to be installed).

Additionally, pure Ruby gems don’t need to execute any code on installation.

If we knew that we were installing a pure Ruby gem, it would be possible to relax the “dependencies are installed first” business requirement and get even more performance increases.

The above a -> b -> c case could install all three gems in parallel since none of them execute Ruby code during installation.

I would propose we split installation in to 4 discrete steps:

- Download the gem

- Unpack the gem

- Compile the gem

- Install the gem

Downloading and unpacking can be done trivially in parallel. We should unpack the gem to a temporary folder so that if the process crashes or the machine loses power, the user isn’t stuck with a half-installed gem. After we unpack the gem, we can discover whether the gem is a native extension or not. If it’s not a native extension, we “install” the gem simply by moving the temporary folder to the “correct” location. This step could even be a “hard link” step as discussed in the next point.

If we discover that the gem is a native extension, then we can “pause” installation of that gem until its dependencies are installed, then resume (by compiling) at an appropriate time.

Side note: gel, a Bundler alternative, works mostly in this manner today.

Here is a timing of the a -> b -> c case from above:

> rm -f Gemfile.lock; time gel install

Fetching sources....

Resolving dependencies...

Writing lockfile to /Users/aaron/git/gemserver/app/Gemfile.lock

Installing c (1.0.0)

Installing a (1.0.0)

Installing b (1.0.0)

Installed 3 gems

________________________________________________________

Executed in 4.07 secs fish external

usr time 289.22 millis 0.32 millis 288.91 millis

sys time 347.04 millis 1.36 millis 345.68 millis

Lets move on to the next point:

Global cache with hardlinks. pip copies packages into each virtual environment. uv keeps one copy globally and uses hardlinks

I think this is a great idea, but I’d actually like to split the idea in two.

First, RubyGems and Bundler should have a combined, global cache, full stop.

I think that global cache should be in $XDG_CACHE_HOME, and we should store .gem files there when they are downloaded.

Currently, both Bundler and RubyGems will use a Ruby version specific cache folder.

In other words, if you do gem install rails on two different versions of Ruby, you get two copies of Rails and all its dependencies.

Interestingly, there is an open ticket to implement this, it just needs to be done.

The second point is hardlinking on installation. The idea here is that rather than unpacking the gem multiple times, once per Ruby version, we simply unpack once and then hard link per Ruby version. I like this idea, but I think it should be implemented after some technical debt is paid: namely implementing a global cache and unifying Bundler / RubyGems code paths.

On to the next point:

PubGrub resolver

Actually Bundler already uses a Ruby implementation of the PubGrub resolver. You can see it here. Unfortunately, RubyGems still uses the molinillo resolver.

In other words you use a different resolver depending on whether you do gem install or bundle install.

I don’t really think this is a big deal since the vast majority of users will be doing bundle install most of time.

However, I do think this discrepancy is some technical debt that should be addressed, and I think this should be addressed via unification of RubyGems and Bundler codebases (today they both live in the same repository, but the code isn’t necessarily combined).

Lets move on to the next section of Andrew’s post:

Where Rust actually matters

Andrew first mentions “Zero-copy deserialization”. This is of course an important technique, but I’m not 100% sure where we would utilize it in RubyGems / Bundler. I think that today we parse the YAML spec on installation, and that could be a target. But I also think we could install most gems without looking at the YAML gemspec at all.

Thread-level parallelism. Python’s GIL forces parallel work into separate processes, with IPC overhead and data copying.

This is an interesting point. I’m not sure what work pip needed to do in separate processes. Installing a pure Ruby, Ruby Gem is mostly an IO bound task, with some ZLIB mixed in. Both of these things (IO and ZLIB processing) release Ruby’s GVL, so it’s possible for us to do things truly in parallel. I imagine this is similar for Python / pip, but I really have no idea.

Given the stated challenges with Python’s GIL, you might wonder whether Ruby’s GVL presents similar parallelism problems for Bundler. I don’t think so, and in fact I think Ruby’s GVL gets kind of a bad rap. It prevents us from running CPU bound Ruby code in parallel. Ractors address this, and Bundler could possibly leverage them in the future, but since installing Gems is mostly an IO bound task I’m not sure what the advantage would be (possibly the version solver, but I’m not sure what can be parallelized in there). The GVL does allow us to run IO bound work in parallel with CPU bound Ruby code. CPU bound native extensions are allowed to release the GVL, allowing Ruby code to run in parallel with the native extension’s CPU bound code.

In other words, Ruby’s GVL allows us to safely run work in parallel. That said, the GVL can work against us because releasing and acquiring the GVL takes time.

If you have a system call that is very fast, releasing and acquiring the GVL could end up being a large percentage of that call.

For example, if you do File.binwrite(file, buffer), and the buffer is very small, you could encounter a situation where GVL book keeping is the majority of the time.

A bummer is that Ruby Gem packages usually contain lots of very small files, so this problem could be impacting us.

The good news is that this problem can be solved in Ruby itself, and indeed some work is being done on it today.

No interpreter startup. Every time pip spawns a subprocess, it pays Python’s startup cost.

Obviously Ruby has this same problem. That said, we only start Ruby subprocesses when installing native extensions. I think native extensions make up the minority of gems installed, and even when installing a native extension, it isn’t Ruby startup that is the bottleneck. Usually the bottleneck is compilation / linking time (as we’ll see in the next post).

Compact version representation. uv packs versions into u64 integers where possible, making comparison and hashing fast.

This is a cool optimization, but I don’t think it’s actually Rust specific.

Comparing integers is much faster than comparing version objects.

The idea is that you take a version number, say 1.0.0, and then pack each part of the version in to a single integer.

For example, we could represent 1.0.0 as 0x0001_0000_0000_0000 and 1.1.0 as 0x0001_0001_0000_0000, etc.

It should be possible to use this trick in Ruby and encode versions to integer immediates, which would unlock performance in the resolver. Rust has an advantage here - compiled native code comparing u64s will always be faster than Ruby, even with immediates. However, I would bet that with the YJIT or ZJIT in play, this gap could be closed enough that no end user would notice the difference between a Rust or Ruby implementation of Bundler.

I started refactoring the Gem::Version object so that we might start doing this, but we ended up reverting it because of backwards compatibility (I am jealous of uv in that regard).

I think the right way to do this is to refactor the solver entry point and ensure all version requirements are encoded as integer immediates before entering the solver.

We could keep the Gem::Version API as “user facing” and design a more internal API that the solver uses.

I am very interested in reading the version encoding scheme in uv.

My intuition is that minor numbers tend to get larger than major numbers, so would minor numbers have more dedicated bits?

Would it even matter with 64 bits?

Wrapping this up

I’m going to quote Andrew’s last 2 paragraphs:

uv is fast because of what it doesn’t do, not because of what language it’s written in. The standards work of PEP 518, 517, 621, and 658 made fast package management possible. Dropping eggs, pip.conf, and permissive parsing made it achievable. Rust makes it a bit faster still.

pip could implement parallel downloads, global caching, and metadata-only resolution tomorrow. It doesn’t, largely because backwards compatibility with fifteen years of edge cases takes precedence. But it means pip will always be slower than a tool that starts fresh with modern assumptions.

I think these are very good points. The difference is that in RubyGems and Bundler, we already have the infrastructure in place for writing a “fast as uv” package manager. The difficult part is dealing with backwards compatibility, and navigating two legacy codebases. I think this is the real advantage the uv developers had. That said, I am very optimistic that we could “repair the plane mid-flight” so to speak, and have the best of both worlds: backwards compatibility and speed.

I mentioned at the top of the post I would address “rewrite it in Rust”, and I think Andrew’s own quote mostly does that for me. I think we could have 99% of the performance improvements while still maintaining a Ruby codebase. Of course if we rewrote it in Rust, you could squeeze an extra 1% out, but would it be worthwhile? I don’t think so.

I have a lot more to say about this topic, and I feel like this post is getting kind of long, so I’m going to end it here. Please look out for part 2, which I’m tentatively calling “What makes Bundler / RubyGems slow?” This post was very “can we make RubyGems / Bundler do what uv does?” (the answer is “yes”). In part 2 I want to get more hands-on by discussing how to profile Bundler and RubyGems, what specifically makes them slow in the real world, and what we can do about it.

I want to end this post by saying “thank you” to Andrew for writing such a great post about how uv got so fast.